Regression Models

Introduction

- This is our first exposure to machine learning methods. Recall that the three major components of a machine learning system are data, model, and learning algorithm. The goal of an ML algorithm is to learn the right model or hypothesis using the available data such that the model can predict the unseen data. The choice of the model depends on the nature of the problem. In this module, we start exploring a group of ML methods/models that deal with predicting a real-valued output(s) (also called the dependent variable or target). This class of methods is called regression methods.

-

Regression is a fundamental problem in machine learning, and regression problems appear in a diverse range of research areas and applications including time-series analysis, control and robotics (e.g., reinforcement learning), deep learning applications such as speech-to-text, image recognition, etc.

- For a regression problem and in general in any machine learning problem, we need to take into account the following considerations:

- Choice of the right hypothesis (parametric/non-parametric, linear/non-linear models, etc.)

- Model selection (e.g., choosing the right hyper-parameters)

- Choosing a learning algorithm

- Overcoming the overfitting (if the model is memorizing the training data and cannot be generalized to the test data)

- Choice of loss function (how to choose the loss function according to the underlying probabilistic model)

- Uncertainty modeling (if the model parameters are deterministic or random)

-

In this module, we start with reviewing some statistical assumptions for regression problems and then focus on studying different types of linear algorithms (i.e., the output of the model is linear with respect to its parameters) as the simplest class of regression models. We also talk about some non-linear models. DNN algorithms are deferred to the DNN section. Initially, we go over the parametric regression methods and then discuss some non-parametric models. Now let’s start with a motivating example:

-

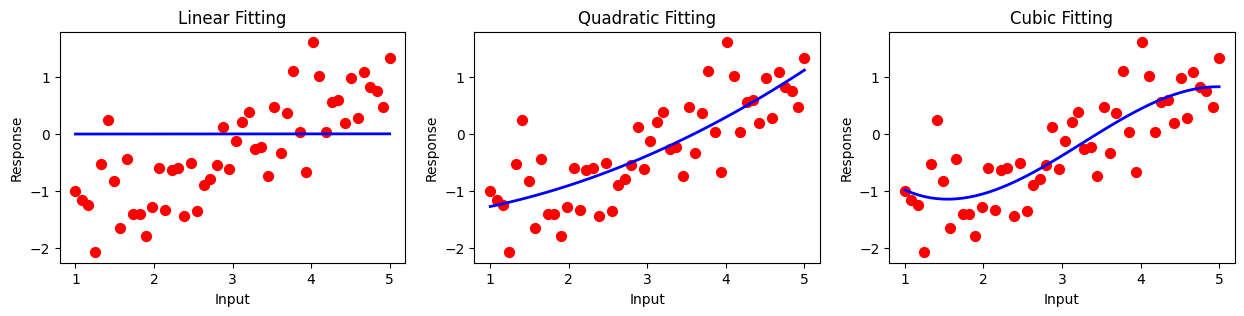

Consider the following scatter plot, illustrating 50 data samples in 1-dimension. The x-axis denotes the feature and the output is a scaler real number. For example, The red circles can represent 50 different humidity levels ranging from very dry denoted by 1 to very humid denoted by 5, and \(y_i\)’s denotes the weather temperature in Celsius. We want to build a regression model to predict the temperature for those humidity levels that do not exist in our dataset.

Code

import numpy as np import matplotlib.pyplot as plt n_samples = 50 sigam = 0.5 X = np.linspace(1, 5, n_samples) X = np.expand_dims(X, 1) y = (-np.sin(X) + sigam*np.random.randn(n_samples, 1)) X_lin = np.hstack((np.ones((n_samples, 1)), X)) w_lin = np.linalg.inv(np.matmul(X.T, X))*np.matmul(X.T, y) y_hat_lin = np.matmul(X, w_lin) X_quad = np.hstack((np.ones((n_samples, 1)), X, X**2)) w_quad = np.matmul(np.linalg.inv(np.matmul(X_quad.T, X_quad)), np.matmul(X_quad.T, y)) y_hat_quad = np.matmul(X_quad, w_quad) X_cub = np.hstack((np.ones((n_samples, 1)), X, X**2, X**3)) w_cub = np.matmul(np.linalg.inv(np.matmul(X_cub.T, X_cub)), np.matmul(X_cub.T, y)) y_hat_cub = np.matmul(X_cub, w_cub) plt.figure(figsize=(10,3)) plt.subplot(131) plt.scatter(X, y, color="red", marker=".", s =200) plt.plot(X, y_hat_lin, color="blue", linewidth=2) plt.xlabel("Input") plt.ylabel("Response") plt.title("Linear Fitting") plt.subplot(132) plt.scatter(X, y, color="red", marker=".", s =200) plt.plot(X, y_hat_quad, color="blue", linewidth=2) plt.xlabel("Input") plt.ylabel("Response") plt.title("Quadratic Fitting") plt.subplot(133) plt.scatter(X, y, color="red", marker=".", s =200) plt.plot(X, y_hat_cub, color="blue", linewidth=2) plt.xlabel("Input") plt.ylabel("Response") plt.title("Cubic Fitting") plt.subplots_adjust(right=1.3) plt.show()

- In the above graph, we see three models for predicting the weather temperature. The left panel shows a linear fitting (linear regression), the middle panel illustrates a quadratic prediction, and the right one shows a cubic curve fitting. We can see the limitedness of linear regression for this specific dataset as the trend of the data doesn’t seem to be linear.

Statistical model

- Depending on the nature of the inputs (also called features, independent variables, explanatory variables, or covariates), there are two types of possibilities. If we think that inputs \(\mathbf{X_1}, \mathbf{X_2},\ldots,\mathbf{X_n}\) are random, we have random design. On the other hand, if input points \(\mathbf{x_1}, \mathbf{x_2},\ldots,\mathbf{x_n}\) are considered as deterministic (fixed points), we call it a fixed design. However, the distinction between fixed and random design is significant and has effects on the measure of performance.

Random design

-

In this scenario, we are given observation data, \(\mathcal{D_n}=\{(\mathbf{X_i}, Y_i)\}^n_{i=1}\) which is a set of \(n\) i.i.d. random input-output pairs, with unknown probability distribution \(p(\mathbf{x}, y)\) such that \(\mathbf{X}\in \mathcal{X}\) and \(Y\in\mathcal{Y}\), where \(\mathcal{X}\) and \(\mathcal{Y}\) are the input and output domains, respectively (e.g., \(\mathcal{X}=\mathbb{R}^p, \mathcal{Y}=\mathbb{R}\)). The \(i^{th}\) data sample, \(\mathbf{X_i}\in \mathbb{R}^p\) is a \(p\)-dimensional random vector. We are asked to find a function \(f:\mathcal{X}\rightarrow\mathcal{Y}\) that maps any test point \(\mathbf{X}^{*}\) to the corresponding \(Y^{*}\) (please note that \( (\mathbf{X}^{*}, Y^{*})\sim p(\mathbf{x}, y)\)). What this means that we hope that we can learn a predictor (sometimes called an estimator) \(\hat{f} := \hat{f}_n := \hat{f}_n(\mathcal{D}_n)\) as a function of our data that generalizes well to the unseen data (e.g., test data). Please note that \(\mathcal{D}_n\) is one specific random set; hence, by changing our data set, the estimator \(\hat{f}\) will also be changed; as a result, \(\hat{f}\) is a random variable.

- Our approach to finding the estimator \(\hat{f}\) is to assume that the observation data has been corrupted by some additive noise (aka observation noise), and we are going to adopt a probabilistic approach and model the noise using a likelihood function. Consequently, we can use the maximum likelihood principle to find \(\hat{f}\).

- For most of our problems, we consider a real-valued (scalar value) response (output). A similar approach usually works for the vector-valued outputs.

- For regression problems, the observation noise is generally modeled as Gaussian noise; hence, we have the following likelihood function:

\[p(Y^{*}|\mathbf{X}^{*}=\mathbf{x}^{*}) =\mathcal{N}(Y^{*} | f(\mathbf{x}^{*}), \sigma^2)\]

- This implies the following relationship between a generic input random vector \(\mathbf{X}\) and its random output \(Y\) with the joint distribution \(p\) (for notation simplicity, we use \((\mathbf{X}, Y)\) instead of the test point \((\mathbf{X}^{*}, Y^{*})\)):

\[Y = f(\mathbf{X}) + \epsilon\]

- \(\epsilon\) is the observation noise and is distributed as \(\epsilon\sim\mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2)\).

- For models we discuss here, we assume that the observation noise is statistically independent of our data, \(\mathbf{X}, Y\).

-

So, finding the estimator \(\hat{f}\) boils down to estimating the mean of the Gaussian distribution using training data. To this end, we use the maximum likelihood approach. The negative log-likelihood (NLL) is given by \[\text{NLL}(f) = \frac{1}{2}\log\sigma^2 + \frac{(Y - f(\mathbf{X}))^2}{2\sigma^2} + \text{cons.}\]

- Please note that, unlike our convention, we have used random \(\mathbf{X}\) and \(Y\) instead of their realization in the above NLL.

-

If we assume \(\sigma^2\) is knowm, minimizing the NLL is equivalent to minimizing \(\frac{(Y - f(\mathbf{X}))^2}{2\sigma^2}\). This is the squared loss. As we have discussed in the Statistics section (link), the measure of fitness is given by the expected risk, considering the expected performance of the algorithm (model) with respect to the chosen loss function. As a result, our estimator is the solution to the following optimization problem: \[f^{*} = \text{argmin}_{\hat{f}}\mathbb{E} \big{(}Y - \hat{f}(\mathbf{X})\big{)}^2 = \text{argmin} _{\hat{f}}\mathbb{E} _{\mathcal{D}_n} \mathbb{E} _{\mathbf{X}, Y} \big{(}Y - \hat{f}(\mathbf{X})\big{)}^2|\mathcal{D}_n\big{)}\]

- Where the risk is given by \( \mathcal{R}(\hat{f}) = \mathbb{E} _{\mathbf{X}, Y} \big{(}Y - \hat{f}(\mathbf{X})\big{)}^2 \).

- In the above likelihood expression, note that we have used \(\hat{f}\) instead of \(f\). This is because we have written the likelihood function using our training data which results in an estimator \(\hat{f}\) (not necessarily the function used in our statistical model). \[\mathbb{E} \big{(}Y - \hat{f}(\mathbf{X})\big{)}^2 = \int_{\mathcal{X}\times\mathcal{Y}}\big{(}y - \hat{f}(\mathbf{x})\big{)}^2 p(\mathbf{x}, y)d\mathbf{x}dy\]

- We note that the inner expectation (the risk) is a random variable as \(\hat{f}\) is a r.v.

-

It can be shown that the optimal regression function which minimizes the above expected risk is given by \(f^*(\mathbf{x}) = \mathbb{E}\big{(}Y|\mathbf{X}=\mathbf{x}\big{)}\).

Proof

Using the Law of Iterated Expectations: \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \hspace{0.4cm}\mathbb{E} \big{(}Y - \hat{f}(\mathbf{X})\big{)}^2 &= \mathbb{E}_{\mathbf{X}}\Big{(}\mathbb{E} _{Y|\mathbf{X}}\big{(}Y-\mathbb{E}\big{(}Y|\mathbf{X}=\mathbf{x}\big{)} + \mathbb{E}\big{(}Y|\mathbf{X}=\mathbf{x}\big{)} - \hat{f}(\mathbf{X})\big{)}^2 |\mathbf{X}=\mathbf{x}\Big{)} \\ & = \mathbb{E} _{\mathbf{X}}\Big{(}\mathbb{E} _{Y|\mathbf{X}}\big{(}Y - \mathbb{E}\big{(}Y|\mathbf{X}=\mathbf{x}\big{)}^2|\mathbf{X}=\mathbf{x}\big{)} \\ & \hspace{+1cm}+ 2\mathbb{E} _{Y|\mathbf{X}}\big{(}\big{(}Y - \mathbb{E}\big{(}Y|\mathbf{X} = \mathbf{x}\big{)}\big{)}\big{(}\mathbb{E}\big{(}Y|\mathbf{X}=\mathbf{x}\big{)} - \hat{f}(\mathbf{X})\big{)}|\mathbf{X} = \mathbf{x}\big{)} \\ & \hspace{+2cm} + \mathbb{E} _{Y|\mathbf{X}=\mathbf{x}}\big{(}\mathbb{E}\big{(}Y|\mathbf{X}=\mathbf{x}\big{)}-\hat{f}(\mathbf{X})\big{)}^2|\mathbf{X}=\mathbf{x}\big{)}\Big{)} \\ & = \mathbb{E} _{\mathbf{X}}\Big{(}\mathbb{E} _{Y|\mathbf{X}}\big{(}Y- \mathbb{E}\big{(}Y|\mathbf{X}=\mathbf{x}\big{)}|\mathbf{X}=\mathbf{x}\big{)}^2 \\ & \hspace{+1cm}+ 2\mathbb{E} _{Y|\mathbf{X}}\big{(}\mathbb{E}\big{(}Y|\mathbf{X}=\mathbf{x}) -\hat{f}(\mathbf{X}\big{)}\big{)}|\mathbf{X} = \mathbf{x}\big{)}\times 0 \\ & \hspace{+2cm} + \mathbb{E} _{Y|\mathbf{X}=\mathbf{x}}\big{(}\mathbb{E}\big{(}Y|\mathbf{X}=\mathbf{x}\big{)} - \hat{f}(\mathbf{X})\big{)}^2|\mathbf{X}=\mathbf{x}\Big{)} \\ & \hspace{0cm} \Longrightarrow \mathbb{E} \big{(}Y - \hat{f}(\mathbf{X})\big{)}^2 \geq \mathbb{E}\big{(}Y - \mathbb{E}\big{(}Y|\mathbf{X}=\mathbf{x}\big{)}\big{)}^2 \\\\ & \hspace{-4cm} \text{Where the minimum in the last inequality is achieved if we choose}~ \hat{f}(\mathbf{x})=\mathbb{E}\big{(}Y|\mathbf{X}=\mathbf{x}\big{)}.\blacksquare \end{aligned} \end{equation}

-

If we plug in the minimizer, \(\mathbb{E}\big{(}Y|\mathbf{X}=\mathbf{x}\big{)}\) in the expected risk expression, we find the following Bias-Variance trade-off: \[\mathbb{E} \big{(}Y - \hat{f}(\mathbf{X})\big{)}^2 = \sigma^2 + \text{Bias}^2(\mathbf{X}) + \text{Var}(\mathbf{X})\]

- Where

- \(\text{Bias}(\mathbf{X}) = \mathbb{E}\big{(}\hat{f}(\mathbf{X})\big{)} - f(\mathbf{X})\)

- \(\text{Var}(\mathbf{X}) = \mathbb{E}\Big{(}\mathbb{E}\big{(}\hat{f}(\mathbf{X})\big{)} - f(\mathbf{X})\Big{)}^2\)

- \(\sigma^2 = \mathbb{E}\big{(}Y-f(\mathbf{X})\big{)}\)

- \(\sigma^2\) is called irreducible error since it is always there as one of the main components in our statistical model.

- In fact, the above expression for \(\sigma^2\) is the MLE of the \(\sigma^2\). If we wanted to estimate it from NLL (by taking derivative w.r.t. \(\sigma^2\) and equating it with zero), we would find the same expression.

- The Bias-Variance trade-off states that we cannot decrease both the bias and the variance of our estimator at the same time. Estimators with higher bias tend to underfit the data; while models with higher variance overfit the training data. We’ll talk about this more later.

Fixed design

- In the fixed design, there is no concept of the marginal distribution of \(p(\mathbf{x})\). Rather, the design points \(\mathbf{x_1}, \mathbf{x_2},\ldots,\mathbf{x_n}\) are considered deterministic, and the goal is to estimate \(f\) only at these points. In this case, the covariance structure of the design points is completely known and we don’t need to estimate it, making the conditions simpler for studying other techniques such as dimension reduction. The fixed design is sometimes called denoising since we want to recover \(f(\mathbf{x_1}), f(\mathbf{x_2}),\ldots,f(\mathbf{x_n})\) given the noisy (random) observations, \(Y_1, Y_2, \ldots, Y_n\). However, the fixed design does not directly address the generalization (out-of-sample prediction).

- Here, we again use the Gaussian noise model for our observation, i.e., \(Y_i = f(\mathbf{x_i}) + \epsilon_i\), where \(\epsilon_i\overset{i.i.d}{\sim}\mathcal{N}(o, \sigma^2)\) for \(i=1,2,\ldots,n\).

- The input points \(\mathbf{x_1}, \mathbf{x_2},\ldots,\mathbf{x_n}\) will usually be represented in the matrix format denoted by \( \mathrm{X}\in \mathbb{R}^{n\times p}\). Please pay attention to the notation of the deterministic matrix we have already introduced (link).

- Using the above Gaussian assumption for the observation noise and using the squared loss, we can write the expected risk (as a measure of performance):

\[ \mathbb{E}\Big{[}\mathcal{R}(\hat{f})\Big{]} = \mathbb{E}\Big{[}\text{MSE}(\hat{f})\Big{]} = \mathbb{E}\Big{[} \frac{1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^n(\hat{f}(\mathbf{x_i}) - f(\mathbf{x_i}))^2\Big{]}\]

- The expectation is taken w.r.t the randomness of \(\hat{f}\) or data samples. That is, we want a best \(\hat{f}\) to perform well, on average, over all realizations of our data distribution.

- We assume the fixed design scenario for the following methods unless stated otherwise.

Parametric and non-parametric models

-

Parametric models. One way to solve the above problem is to assume that our estimator \(\hat{f}: \mathbb{R}^p\rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) has a parametrix form, \(\hat{f}(\mathbf{x}, \pmb{\theta})\), where \(\pmb{\theta}\in \mathbb{R}^k\) denotes a set of parameters such that \(k = o(n)\), that is, \(k\) doesn’t grow with the number of samples. If \(k=O(p)\), the model is called under-parametrized (i.e., we are in low-dimensional space), while models with \(k \gg p\) are called over-parametrized (i.e., we are in high-dimensional space). One example of the over-parametrized models is Deep Neural Networks (DNNs).

-

Non-parametric models.

Parametric Models

- We discuss the following parametric models:

- Linear Regression

- Polynomial Regression

- Ridge Regression

- LASSO

- Group LASSO

- Kernel Method in Regression

- Support Vector Regression (SVR)

- Bayesian Linear Regression

Linear Regression

- We first focus on the linear regression models; as a result, we may assume that the output is a linear function of the input. Unless otherwise stated, we assume the fixed design for linear regression models.

- We note that this is just an assumption, and it may not be valid or realistic, but certainly, the linear models are the simplest model we can start with.

- Hence, \(\hat{f}(\mathbf{x}, \pmb{\theta}) = b + \mathbf{w}^T\mathbf{x}\), where we consider the case \(k=p\) and the low-dimensional space, i.e., \(n\geq p\) (We’ll talk about the high dimensional regime later). Accordingly, the likelihood function is given by:

\[p(Y|\mathbf{x}) =\mathcal{N}(Y | b + \mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x}, \sigma^2)\]

- Here, \(\pmb{\theta} = (\mathbf{w}, b, \sigma^2)\) denotes all the parameters of the model.

- The vector of parameters \(w_1, w_2,\ldots, w_p\) are known as the weights or regression coefficients. Each coefficient \(w_i\) specifies the change in the output we expect if we change the corresponding input feature \(x_i\) by one unit.

- The coefficient \(b\) is called the offset or bias term. This captures the unconditional mean of the response, \(b = \mathbb{E}(y)\), and can be used as a baseline for regression problems. In most cases, we absorb the bias term into the vector \(\mathbf{w}\) and consider the coefficient vector as \(\pmb{\theta} = [b, w_1, w_2, \ldots, w_p]^T\). This implies that number 1 is appended from the left to all input samples, i.e., \(\mathbf{x_i} = [1, x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_p]^T\) for all \(i=1,2,\ldots,n\). So, in the matrix notation, our observation model is given by:

\[\mathbf{Y} = \mathrm{X}\pmb{\theta} + \pmb{\epsilon}\]

- Where \(\pmb{\epsilon} = [\epsilon_1, \epsilon_2,\ldots,\epsilon_n]^T\), \(\epsilon_i\sim\mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2)\), \(\mathrm{X}\in\mathbb{R}^{n\times p}\) denotes the covariate matrix, and \(\mathbf{Y}\in\mathbb{R}^n\) is the random vector of the response.

- When \(p=1\), the regression problem is called simple linear regression, and if \(p>1\), it is called multiple linear regression. Also, when the output is a vector, the regression problem is called multivariate linear regression.

-

As mentioned before, the linear model is called linear because of the linear relationship between the output and the input features. In general; however, a straight line will not provide a good fit to the observation data. In this case, one can apply a nonlinear transformation to the input features to obtain new features of \(\phi(\mathbf{x})\), and make the output-input relation linear, i.e., \(y=\mathbf{w}^T \phi(\mathbf{x})\). This relationship is still linear, so we can study it in the context of linear regression models. We’ll come back to this when we talk about kernel methods.

- Before discussing the training of the linear model (fitting observation data), let’s review the fundamental assumptions in a linear regression model.

- The key property of the model is that the expected value of the output is assumed to be a linear function of the input, i.e., \(\mathbb{E}(Y|\mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x}\), which makes the model easy to interpret, and easy to fit data.

- The feature vectors do not correlate with each other. If they are related to each other, then the term multicolinearity is used.

- The noise and the observation are statistically independent.

- The observation noise is assumed to be Gaussian and Stationary across all samples. This property is sometimes called Homoscedasticity.

Learning the linear model (fitting the data with a hyperplane)

- To learn the linear model, we follow the same procedure of minimizing NLL: \[\text{NLL}(\pmb{\theta}) = \frac{n}{2}\log\sigma^2 + \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n(y_i - \pmb{\theta}^T\mathbf{x_i})^2}{2\sigma^2} + \text{cons.}\]

- To find the minimizer \(\pmb{\theta}\), we assume that \(\sigma^2\) is fixed. As a result, we need to minimize the Residual Sum of Squares (RSS) defined below:

\[\text{RSS}(\pmb{\theta}) = \frac{1}{2}\sum_{i=1}^n(y_i - \pmb{\theta}^T\mathbf{x_i})^2 = \frac{1}{2}||\mathbf{y} - \mathrm{X}\pmb{\theta}||_2^2\]

- Where \(\mathbf{y} = [y_1, y_2,\ldots, y_n]^T\) is a realization of the random vector \(\mathbf{Y}\).

- This is the risk expression (MSE equation) for the fixed design setup (not the expected risk). Now if we take the derivative w.r.t to \(\pmb{\theta}\), we obtain the gradient: \[\nabla_{\pmb{\theta}}\text{RSS}(\pmb{\theta}) = \mathrm{X}^T\mathrm{X}\pmb{\theta} - \mathrm{X}^T\mathbf{y}\]

- Now setting the gradient to zero, we find the optimal solution called Normal Equation or ordinary least squares (OLS) solution: \[\hat{\pmb{\theta}} = \pmb{\theta}_{mle} = (\mathrm{X}^T\mathrm{X})^{-1}\mathrm{X}^T\mathbf{y}\]

- There are three important observations here:

- The \(\hat{\pmb{\theta}}\) is a random vecotr since the response \(Y_i\)’s are random.

- The matrix \( (\mathrm{X}^T\mathrm{X})^{-1}\mathrm{X}^T\) is the (left) psuedo-inverse introduced (here). This can be seen easily by checking the four conditions.

- The OLS solution for the parameters is unique. To see this, we first note that \(\text{RSS}(\pmb{\theta})\) is a convex function because if we calculate the Hessian of the \(\text{RSS}(\pmb{\theta})\), we obtain \(\mathcal{H} = \nabla_{\pmb{\theta}}^2\text{RSS}(\pmb{\theta}) = \mathrm{X}^T\mathrm{X} \succeq 0\). That is, the Hessian is, in general, a positive semi-definite. Now, since we have assumed that the features are linearly independent, then the matrix \(\mathrm{X}\) is a full-column rank. On the other hand, we know that \(rank(\mathrm{X}) = rank(\mathrm{X}^T\mathrm{X})= p\); hence, \(\mathrm{X}^T\mathrm{X}\) is a full-rank matrix; as a result, the Hessian is positive definite, i.e., \(\mathcal{H}\succ 0\). This means that the \\hat{\pmb{\theta\)}\) satisfies the condition for being a unique global minimum of the convex objective function, \(\text{RSS}(\pmb{\theta})\). From this, we conclude that the square matrix \( (\mathrm{X}^T\mathrm{X})\) is an invertible matrix.

- Geometric intrepretation of the least squares